The History of the Ouija Board: From Spiritualist Tool to Horror Game

Introduction

The Ouija board did not begin its career as a harbinger of cinematic possession or whispered adolescent dares. It emerged at the intersection of late nineteenth‑century American spiritualism, entrepreneurial patent seekers, family parlour entertainment and mass‑market branding. This article follows a documented historical arc: early planchette writing practices; the leap to a fixed alphabet board; the Kennard Novelty Company’s commercialisation; William Fuld’s influential stewardship; the mid‑twentieth century reframing from domestic amusement to occult concern; and finally the surge of fear narratives following key horror media releases and moral panics. Rather than focusing on session technique or safety protocol (covered separately in our practical guide), we concentrate here on verifiable cultural, legal, marketing and media milestones that transformed an ordinary novelty into a durable popular icon. We also examine how shifting interpretations mirrored broader anxieties: death, war casualties, changing religious landscapes, youth culture, and media sensationalism. By the end you will have a grounded timeline separating substantiated history from embellished folklore and learn why the board’s meaning keeps evolving.

Basic Definition and Historical Overview

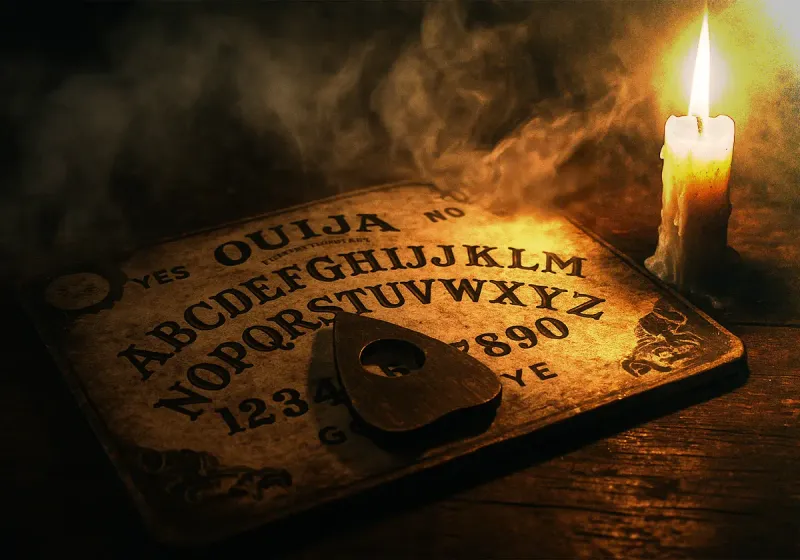

A Ouija or “talking board” is a flat surface printed with the alphabet, numerals 0–9, affirmative/negative words (YES / NO) and a farewell (GOODBYE) used with a small pointer called a planchette. The specific pairing of a static alphanumeric layout and a freely moving indicator coalesced during the 1880s–1890s in the United States while interest in spiritualist séances was still strong decades after the movement’s 1848 Fox Sisters publicity catalyst. Earlier related practices included table tipping, rapping codes and the separate planchette device—a small wheeled platform holding a pencil that produced automatic writing when participants rested their hands upon it (popular from the 1850s onward). The talking board innovation effectively streamlined automatic writing by removing the pencil: letters were selected visually rather than traced.

Commercial origin points centre on Baltimore, Maryland. In 1890 a group of investors formed what became the Kennard Novelty Company to manufacture and market the board nationally. Elijah J. Bond is associated with a US patent application; an American patent (commonly referenced as granted in 1891) protected aspects of the board’s design and marketing claims. Subsequent consolidation placed production and branding prominence with William Fuld, who—through interviews and promotional language—positioned himself as the “inventor” (a claim that simplified a more collaborative genesis). Early advertising framed the board as both mystical and a respectable parlour amusement, promising answers to questions “about the past, present and future.”

Key early historical milestones (verifiable through period newspapers, trade catalogues and patent records):

- 1850s–1860s: Independent planchette writing devices spread in Europe and North America.

- Late 1880s: Regional experimentation with lettered boards used in spiritualist circles.

- 1890: Organisation of the Kennard Novelty Company.

- 10 Feb 1891: US patent granted to Elijah J. Bond for a “Talking Board” device (referenced in modern patent archives).

- 1890s–1900s: Rapid expansion; boards sold as light entertainment more than solemn ritual objects.

- 1910s–1920s: William Fuld era branding; export and domestic distribution scale up; coverage in mainstream press emphasises curiosity and sales volume.

The board’s early identity was neither uniformly sinister nor strictly sacred; it inhabited a liminal space alongside other parlour diversions like card games and word puzzles, while borrowing spiritualist rhetoric sufficient to intrigue consumers.

Scientific and Skeptical Perspectives (Historical Framing)

Across its history, explanations for the board’s operation have frequently reflected concurrent psychological and physiological discourse rather than purely supernatural speculation. Nineteenth‑century researchers studying automatism—investigating how seemingly unconscious motor actions manifest—provided a naturalistic framework that newspapers occasionally popularised alongside commercial adverts. Figures such as William B. Carpenter (ideomotor action) and earlier Michel Eugène Chevreul (pendulum experiments) supplied conceptual tools to reinterpret séance phenomena as unconscious muscular influence guided by expectation.

During the early twentieth century, as scientific psychology professionalised, laboratory interest concentrated on suggestion, dissociation and subconscious processing. These domains offered secular narratives for “mysterious” board results. Period magazine articles sometimes juxtaposed commercial enthusiasm with expert caution suggesting that the user’s own mind produced the messages. After major wars (notably the First World War), surges in bereavement intensified public desire for contact, yet sceptical commentary still foregrounded unconscious ideation and chance letter selection. Mid‑century rationalist and debunking organisations later republished earlier ideomotor critiques to counter renewed sensationalism.

Thus, rather than a linear triumph of supernatural over scientific framing or vice versa, the board’s history shows a recurrent oscillation: each cultural wave of heightened interest (post‑war grief, horror film release, moral panic) prompts renewed restatement of psychological accounts already available decades prior.

Believer and Experiencer Perspectives Through Time

Believer interpretations have also shifted historically, influenced by broader metaphysical fashions:

- Late 1800s: Spiritualist users considered the board an efficient variation on earlier séance tools—another “instrument” for discarnate communication, often employed alongside trance mediums.

- Early 1900s: Some accounts framed the board as a quasi‑scientific interface, emphasising neutrality and experimental potential consistent with contemporaneous psychical research ambitions.

- Interwar Period: Reports (particularly in local newspapers) highlight domestic consolation; families sought personal messages, reflecting large‑scale bereavement patterns.

- Mid‑Twentieth Century: Popular culture folded the board into a generalised occult revival; mail‑order catalogues sometimes grouped it with astrology sets and fortune‑telling paraphernalia.

- Post 1970s: Horror media depictions introduced themes of possession, malevolent entities and escalating hauntings; believer communities began integrating cautionary folklore (narratives of “opening doors” and “attachments”).

- Contemporary Digital Era: Online forums host hybrid interpretations—mixing classic spiritualism with energy work, thoughtform creation ideas and modern paranormal investigation jargon.

Throughout these phases, experiential claims often emphasised personalised validation (names, dates, mood impressions). The historical continuity lies less in any single explanatory model and more in the board’s role as a narrative canvas onto which prevailing hopes and anxieties are projected.

Research and Evidence Analysis (Historical Sources & Cultural Studies)

Rigorous primary research into the board’s cultural trajectory draws on a mosaic of source types: patent filings, trademark records, trade advertisements, newspaper archives, catalogue listings, court or business documents (for corporate transitions), and later film marketing materials. Academic analyses in folklore and media studies examine how objects accrue mythic valence through storytelling loops. The Ouija board’s shift from neutral novelty to putative occult risk parallels documented cycles of moral concern about youth leisure technologies (comic books mid‑20th century, video games late 20th century, internet forums early 21st century).

Key evidence‑supported transitions:

- Commercial Formation: Surviving corporate documents and patents anchor the 1890–1891 birth of the mass‑market board; multiple stakeholders contributed, countering simplified sole‑inventor myths.

- Branding & Attribution: William Fuld’s successful self‑promotion reoriented public perception, evidenced by period interviews crediting him personally despite documented earlier collaborators.

- Post‑War Demand: Newspaper sales references and anecdotal reporting indicate spikes in use linked to wartime bereavement waves (a pattern echoed across various spiritualist practices).

- Corporate Acquisition: Mid‑1960s acquisition by a major game company (Parker Brothers; later under Hasbro) integrated the board into mainstream toy and game catalogues, broadening distribution while subtly reframing it as youth entertainment.

- Cinematic Reframing: The 1973 release of a landmark possession‑themed film (widely credited with shifting cultural fear frameworks) recontextualised board imagery as an early catalyst of peril; subsequent horror media serialised this motif.

- Moral Panic Era: 1980s–1990s English‑language media sometimes bundled the board within broader “occult danger” narratives; documented school or church burnings/destructions occasionally appeared in local press (illustrating perception shifts rather than intrinsic object change).

Methodological limitations: Many secondary retellings recycle earlier unverified claims (e.g. embellished séance origin stories or apocryphal early messages). Historians emphasise cross‑checking multiple independent primary sources to avoid citation cascades where repetition masquerades as corroboration. Material culture analysis (examining board construction changes, graphic design evolution, packaging language) also reveals shifts in marketed identity—from ornate Victorian mystique to brightly styled mid‑century game box art and later deliberately “spooky” branding.

Practical Information (Using the History Responsibly)

While practical operation and safety considerations sit outside this article’s purpose, historically informed engagement benefits researchers, collectors and casual readers alike:

- Distinguish Patent Fact from Marketing Myth: Treat inventor claims printed on boxes as brand narrative; corroborate via patent numbers and corporate filings.

- Date Boards by Materials & Typography: Early examples often feature thicker wooden boards, varnished finishes and serif letterforms; later mass‑market versions favour cardboard substrates and simplified sans‑serif designs. This aids authenticity assessment for collectors.

- Document Provenance: Photograph packaging, note purchase locations, retain receipts or auction listings; future researchers rely on traceable ownership chains.

- Contextualise Personal Accounts: When evaluating a historical session anecdote, ask: Is the source contemporary to the event or a decades‑later recollection? Are there independent witnesses? Was any content logged verbatim or only summarised post hoc?

- Avoid Retroactive Fear Injection: Recognise that early users frequently treated the board as neutral entertainment. Projecting later horror tropes backwards distorts interpretive clarity.

- Integrate Interdisciplinary Sources: Combine business history (distribution channels), religious studies (responses from clergy), media studies (film/television influence), and psychology (interpretation frameworks) for a richer narrative.

- Internal Linking for Deeper Practice Guidance: For session technique, ethical participation and misconception analysis see our separate guide: How to Use a Ouija Board Safely: Rules and Myths. This avoids duplicating operational details here.

Conclusion and Current Understanding

The Ouija board’s history is a study in cultural repurposing. Born amid spiritualism’s blend of consolation, curiosity and performative séance practice, it was engineered into a portable, marketable novelty through coordinated entrepreneurial efforts. Its meanings have never been static: early parlour amusement; post‑war grief coping aid; mid‑century branded family game; late twentieth‑century horror emblem; contemporary hybrid of nostalgic toy, paranormal investigation prop and internet meme object. Across each phase, previously articulated psychological explanations for its functioning coexisted with renewed supernatural interpretations, demonstrating that explanatory frameworks recycle with audience turnover and media amplification.

Understanding this layered history does not adjudicate metaphysical claims; instead it clarifies how commercial strategy, media depiction and social anxiety sculpt an artefact’s perceived ontological status. Appreciating the board historically encourages methodological caution (source verification, myth filtration) while illuminating broader patterns in how societies ritualise uncertainty and grief. Its endurance reflects adaptability: a cheap, interactive storytelling device continually reinterpreted to mirror prevailing narrative appetites. Seen through this lens, the Ouija board is less an occult constant than a cultural mirror—its shifting reputation tracing over a century of changing hopes, fears and entertainment economies.

Selected Primary / Reputable Source Types to Consult (encouraged for further research): US Patent archives (e.g. Bond 1891 talking board patent), period Baltimore newspaper adverts (1890–1892), early twentieth‑century trade catalogues, mid‑century Parker Brothers catalogues, film marketing ephemera (1970s), folklore and media studies analyses of moral panics. Avoid relying solely on unsourced anecdotal blog repostings.