What is a Spirit Box and How Does it Work?

Introduction

If you watch modern paranormal investigation videos you will almost certainly encounter a fast chattering device spitting out chopped syllables while investigators ask questions. Someone leans in, a clipped word emerges, and the group reacts. This gadget is commonly called a spirit box. Proponents claim it enables real time two way communication with voices of the dead by providing a stream of audio fragments that can be selectively manipulated. Sceptics counter that it is simply scanning normal broadcast radio and the human brain is doing the pattern assembly.

This article explains exactly what a spirit box is from an electronics and radio perspective, what it actually produces, the principal claimed interaction methods, how investigators attempt to reduce false positives, and the most common interpretive errors. We balance believer viewpoints about apparent contextual replies with scientific and methodological critique. If you are totally new to investigative equipment you may first want to read the broader overview in the Beginner’s Guide to Ghost Hunting Equipment which situates the spirit box within a whole toolkit. Here we drill into one device with a focus on function, usage protocol, limitations, and responsible practice.

Basic Definition and Overview

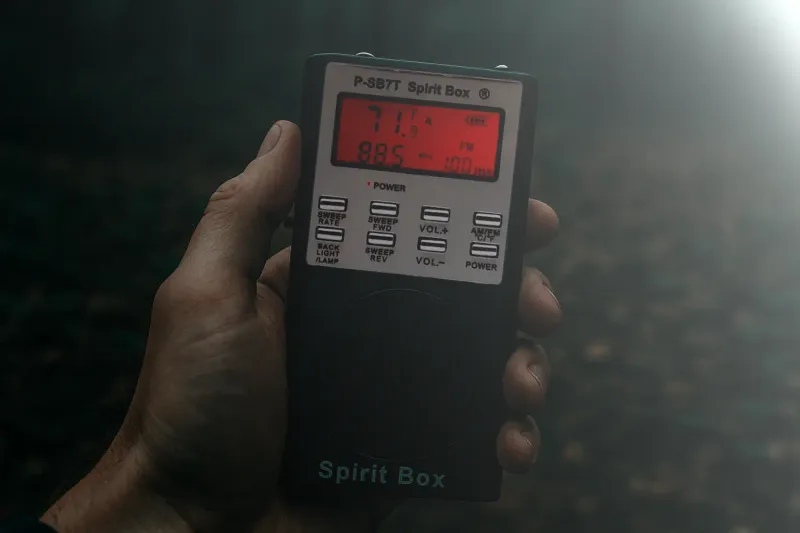

A spirit box (sometimes marketed under assorted brand names or simply called a radio sweep box) is a portable device that rapidly cycles (“sweeps”) through radio frequencies across the AM and/or FM broadcast bands while outputting the resulting demodulated fragments through a speaker or headphones. Most units allow you to set sweep direction (forward/back), sweep speed (milliseconds dwell per frequency step), and band selection. Some add noise reduction, a built in flashlight, or an option to mute the radio carrier while keeping presumed voice frequencies (this usually just applies a simple filter or gate, not a genuine isolation of paranormal content).

What you hear during a session is a concatenation of:

- Snippets of ordinary radio transmissions (music, adverts, DJ speech, news bulletins, emergency service spillover if near overlapping ranges)

- White or pink noise filling gaps between strong stations

- Intermodulation artefacts (overlapping signals creating brief tonal bits)

- Clicks and tuning artefacts from the stepping oscillator

The core premise advanced by believers is that an external discarnate intelligence can influence which syllables surface (by timing, modulation, or subtle energy interaction) to assemble responses. Sceptical perspective holds that given a constant stream of random linguistic fragments and primed expectation, observers will inevitably perceive relevant words (auditory pareidolia) especially for short, high frequency monosyllables (yes, no, name-like sounds).

Historically, the spirit box concept builds on earlier Instrumental Transcommunication (ITC) methods: detuned radios (so called “ghost boxes”) in the late twentieth century, tape and radio feedback loops, and Frank’s Box (an early custom scanning radio). Modern commercial versions miniaturise components and add speed control and simple band pass filtering. No version departs from the basic principle of scanning existing broadcast content. The device does not generate new vocal material ex nihilo; it selects from what is already present on air or from static shaped by electronics noise.

How It Works (Electronics and Signal Path)

- Tuner Front End: A small integrated circuit (often a digitally controlled tuner chip) steps through frequency increments (e.g. 50 kHz FM steps or 10 kHz AM steps) under microcontroller control.

- Local Oscillator and Mixer: Converts the chosen radio frequency to an intermediate frequency (IF) for filtering and demodulation just like a normal radio.

- Demodulation: FM or AM demodulators recover audio from the carrier. If no strong station is present the demodulator outputs mainly noise shaped by the IF bandwidth.

- Sweep Control: Firmware sets dwell time per frequency. Extremely fast sweeps produce chopped, staccato phonemes; slower sweeps yield longer fragments (partial words or multiple syllables from one station).

- Audio Conditioning: Some units add a simple high pass or band pass filter, a noise gate (closing below a threshold), or a low fidelity echo effect. None of these functions conjure novel speech; they just reshape noise and fragment boundaries.

- Output: Speaker or headphone jack. Some boxes include a record function, though many investigators prefer an external digital recorder for archival quality and to maintain an unaltered master file.

Important technical note: Because adjacent stations can bleed when sweeping rapidly, a single perceived syllable might blend two different broadcasters. This can create the illusion of a composite, context fitting word.

Scientific and Sceptical Perspectives

From a critical methodology angle, the spirit box presents multiple statistical and cognitive pitfalls:

- High Base Rate of Intelligible Units: Radio bands are densely populated. Even at night when some stations reduce power there is still abundant speech and music. Random sampling yields lots of phonetic elements.

- Auditory Pareidolia: The brain is tuned to extract meaningful patterns from noise. When primed with an expectation (“Say your name”), ambiguous fragments are more likely to be internally resolved as a name-like sound. Studies of speech in noise demonstrate that top down expectation strongly influences perceived content.

- Selective Memory and Reporting: Sessions often produce a continuous stream of irrelevant sounds; only the seemingly fitting words are highlighted afterwards, creating an impression of focused responsiveness.

- Multiple Comparisons Problem: Dozens of questions asked increase chance of occasional apparent hits without statistical correction.

- Leading Questions and Confirmation Bias: Specific, narrow questions (“Is your name Thomas?”) raise probability that any T sound followed by a vowel will be accepted as confirmation.

- Group Suggestion Dynamics: One participant announcing “It said ‘leave’” biases others to re-map an ambiguous syllable to that interpretation.

- Lack of Blinded Protocol: The operator hears both question and sweep simultaneously; they cannot separate their expectation from perception. Few casual sessions attempt double blind scoring.

A robust sceptical test would involve pre registering a short list of target words, recording sessions, then having blinded independent reviewers score whether those words occurred above chance relative to control sweeps without questions. Such structured studies are rare in the public domain. Without them, individual anecdotal hits retain low evidential weight.

Believer and Experiencer Perspectives

Believers argue that simple chance cannot explain certain patterns they have logged. Common claims include:

- Direct Contextual Replies: A location specific term (e.g. a surname on a memorial) emerging within seconds of a related question.

- Sequential Interaction: A series of yes/no responses aligning with a question sequence more consistently than expected randomness.

- Continuation Across Sweeps: A multi syllable word spanning several frequency steps, interpreted as an entity sustaining communication despite the tuner shifting.

- Cross Device Correlation: A perceived word on the spirit box occurring simultaneously with an EMF change or a motion sensor trigger.

- Foreign Language or Obscure Terms: Words that participants assert they did not know at the time but matched later historical research on the site.

Interpretative believer frameworks propose mechanisms such as modulation of electromagnetic fields influencing which stations the tuner emphasises, energy shaping of noise, or selection at the moment of auditory cognition rather than at the hardware level (i.e. a psi-mediated perception hypothesis). These remain hypotheses without broadly accepted experimental demonstration. Nevertheless, consistent personal experiences reinforce practitioner confidence, motivating increasingly elaborate protocols (paired boxes, Faraday bag experiments, randomised sweep speeds) to seek stronger evidence.

Research and Evidence Analysis

Formal peer reviewed literature directly validating spirit box communication is minimal. Instrumental Transcommunication has sporadically appeared in parapsychological journals, typically with exploratory case studies rather than large scale controlled trials. Publicly accessible datasets with raw audio, time stamped questions, and control sweeps are scarce. This scarcity prevents independent replication or statistical meta analysis.

General cognitive science and auditory perception research, while not about paranormal devices specifically, provides relevant context: humans can identify speech patterns in heavily degraded signals; expectation heightens detection of target phonemes. This aligns with sceptical cautions but does not disprove a potential anomalous layer; it simply sets a high bar for discriminating genuine anomaly from psychological filtering.

Some investigators attempt quasi experimental setups:

- Running silent control periods where no questions are asked and comparing lexical density of perceived meaningful words.

- Using word lists sealed in envelopes before the session, later opened to see if any target words surfaced (attempting to pre register criteria).

- Employing independent listeners who review raw audio without knowing questions, then comparing their transcriptions for agreement metrics.

Results of such endeavours are usually informal blog posts or video summaries without raw data, limiting scientific scrutiny. A pathway toward stronger evidence would include: open repository of raw WAV files, published question logs with exact timestamps, pre defined success metrics, and independent multi rater transcription with inter rater reliability statistics. Until that practice becomes common, evidence quality stays low and interpretations remain subjective.

Practical Information (Using a Spirit Box Responsibly)

Core Goals

- Explore whether any apparent contextual audio emerges under controlled conditions.

- Document environmental context and reduce contamination so later reviewers can assess data quality.

- Maintain ethical, respectful tone toward any presumed consciousness.

Recommended Basic Kit

- Spirit box unit with adjustable sweep speed

- External digital recorder (records both questions and output clearly)

- Headphones (closed back) for isolated listening segments

- Notebook or digital log (time, question, perceived response, participants present)

- Optional: second recorder placed at distance for cross comparison

Session Setup

- Survey area. List known radio interference sources (Wi Fi routers, nearby transmitters, metal structures creating reflections).

- Set sweep parameters. Many practitioners select a mid range speed (e.g. 150–250 ms per step) to balance fragment length and variety. Extremely fast sweeps produce more chopped noise, which can increase pareidolia.

- Record baseline: run the box for one minute without questions. Mark this as control.

- Begin question sequence. Ask one question then remain silent allowing several sweep cycles (avoid rapid stacking of questions which obscures potential timing correlation).

- Verbally tag obvious environmental sounds (coughs, chair movement) so they are not misinterpreted later.

- After a block of 5–7 questions, run another silent control minute.

- Log battery level and environmental conditions (temperature, time) for completeness.

Ethical Considerations

Keep language polite. Avoid provocative or confrontational demands. If participants feel distressed, pause. Respect property rules and neighbours (spirit boxes can be loud, potentially causing disturbance).

Proper Usage (Technique Deep Dive)

- Sweep Speed Experimentation: Conduct multiple short sessions at different speeds and log whether apparent clarity differs. Avoid claiming a sweet spot based on a single outing.

- Forward vs Reverse Sweep: Some operators run the radio in reverse frequency order claiming it reduces full words. In practice it simply changes station sequence; it does not prevent fragments of speech. Test claims by comparing lexical output density.

- Headphone Isolation Sessions: One person (blind listener) hears the box via headphones while another silently shows question cards unseen by the listener (no mouth movements). Listener then writes any heard words. Compare matches. This crude blinding helps reduce confirmation bias.

- Tagging Suspected Hits: Instead of reacting immediately (which primes group perception), calmly state the perceived word and time stamp. Later analysis can assess whether it was a valid fragment or misheard.

- Cross Validation: If using two boxes simultaneously on different bands, only treat a word as notable if similar phonetic content emerges within a short window on both (rare, but a stronger test than single box reliance).

Interpretation Guidelines

When evaluating a purported response ask:

- Could the fragment plausibly originate from a normal broadcast (advert, presenter, song lyric)? If yes, mundane explanation takes precedence.

- Was the word predicted or primed by recent conversation? If yes, higher risk of pareidolia.

- Did independent, blinded reviewers (who did not know the question) transcribe the same word? If not, subjective.

- Does the session include documented null periods? Selectively reporting only hits biases perception.

- Is there temporal proximity: does the word appear within 2–3 seconds after the question gap rather than during overlapping speech? Overlap weakens causal interpretation.

- Is the word multi syllabic or unusual (and verifiable in later research) rather than a common short filler? Uncommon content may warrant further controlled replication attempts, still not proof.

Adopt a tier system:

- Tier 0: Common short word, high broadcast likelihood, no independent agreement.

- Tier 1: Slightly longer fragment, some agreement, plausible broadcast source.

- Tier 2: Unusual word, independent agreement, timing match, needs background station check.

- Tier 3: Complex phrase, multiple independent matches, replicated in follow up sessions under partial blinding (rare; still provisional, not conclusive).

Limitations

- Cannot exclude normal station origin without logging frequency list and later cross checking recordings against known broadcasts at that time.

- Cannot generate new audio; only samples existing radio and noise. Any communication claim necessarily involves selective emergence rather than creation.

- Highly susceptible to user expectation and group dynamics.

- Often used in acoustically reflective rooms which colour fragments, increasing misperception.

- Hardware differences (tuner sensitivity, filtering) affect fragment clarity making cross investigator comparisons difficult.

- Lack of calibration standards for sweep speed timing accuracy among consumer models.

Safety Level and Practical Risks

Physical safety risk is low: the device is a standard radio scanner. Main considerations are volume (hearing fatigue), battery overheating (rare with reputable brands), and situational distraction (reduced awareness of surroundings in dark locations). Keep volume moderate, take listening breaks, and maintain situational awareness.

Complementing Other Equipment

Pairing a spirit box with an ambient audio recorder allows post session verification of perceived words. Using an EMF meter concurrently can log whether claimed responsive words coincide with electromagnetic changes, though correlation alone does not indicate causation. A data logger can add environmental context. If you are assembling a toolkit, refer again to the wider Beginner’s Guide to Ghost Hunting Equipment for baseline methods before specialising in more interpretively ambiguous devices like this.

Future Research Directions

Progress toward stronger evidential claims would involve:

- Standardised experimental protocols (pre registered target word lists, randomised silent control intervals).

- Publication of raw audio with synchronised question transcripts and station identification logs.

- Independent multi rater transcription measuring inter rater reliability (e.g. Cohen style agreement metrics) to quantify subjectivity.

- Statistical modelling of expected random word occurrence frequencies for given sweep parameters to provide a benchmark.

- Exploration of machine learning phoneme recognition on raw sweep audio to compare human perceived hits with algorithmic detection (controls for expectation bias).

These steps would not guarantee proof of anomalous communication but would refine signal to noise assessment, making genuine anomalies (if any) more discernible.

Conclusion and Current Understanding

A spirit box is fundamentally a rapid scanning radio producing a mosaic of normal broadcast fragments and noise. Believers interpret occasional context fitting words as evidence of external intelligence manipulating fragment emergence. Sceptics attribute perceived replies to auditory pareidolia, expectation, and statistical inevitability within a dense linguistic stream. Current public evidence lacks the controlled, blinded, reproducible datasets required to elevate claims beyond anecdotal pattern perception.

Used responsibly, the spirit box can serve as a structured prompt device focusing group attention and generating audio logs for later analytical practice. Its greatest value for a disciplined investigator may lie in teaching rigorous documentation, sceptical filtering, and proper control design rather than providing proof of survival. Approach sessions with curiosity, implement controls, archive raw data, and be candid about limitations. Pair the device with foundational good practice outlined in the broader beginner equipment guide to avoid over interpreting random radio noise as meaningful communication.

Internal linking suggestions (ensure final site build includes working links): Link ITC references to any future instrumental-transcommunication explainer, EVP content to an evp-electronic-voice-phenomena article, and methodology notes to a future evidence-evaluation-framework article.